Redundancy has a bad rap. It conjures images of lost jobs, of being the expendable one. But as a creative, redundancy is my secret weapon. It makes me and my creative work resilient.

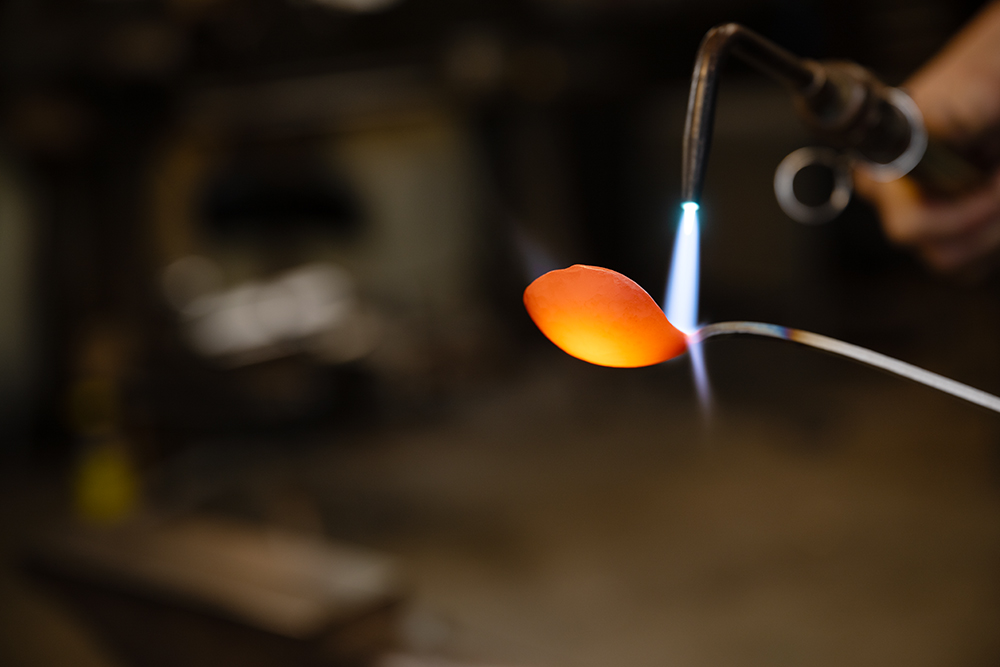

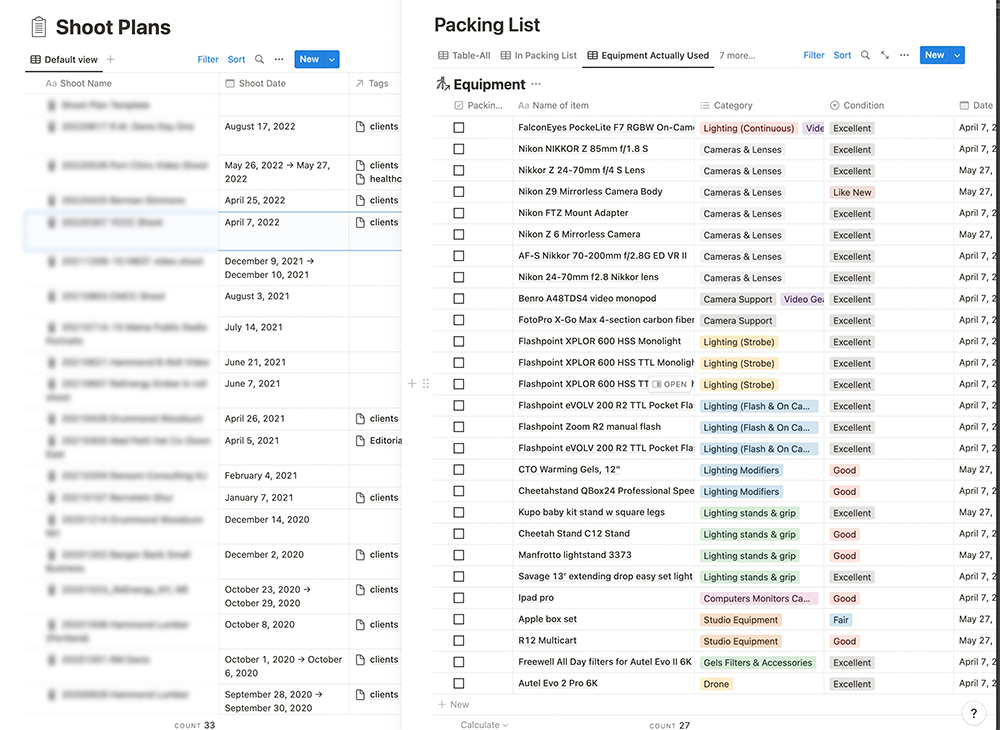

Think about photo gear: cameras, cards, batteries, lights—all need backups. When I’m far from home, a single gear failure can derail a shoot. But the idea goes deeper. Redundant copies of client work, a shortlist of reliable assistants, multiple setups for every shoot—they all are necessary in my world.

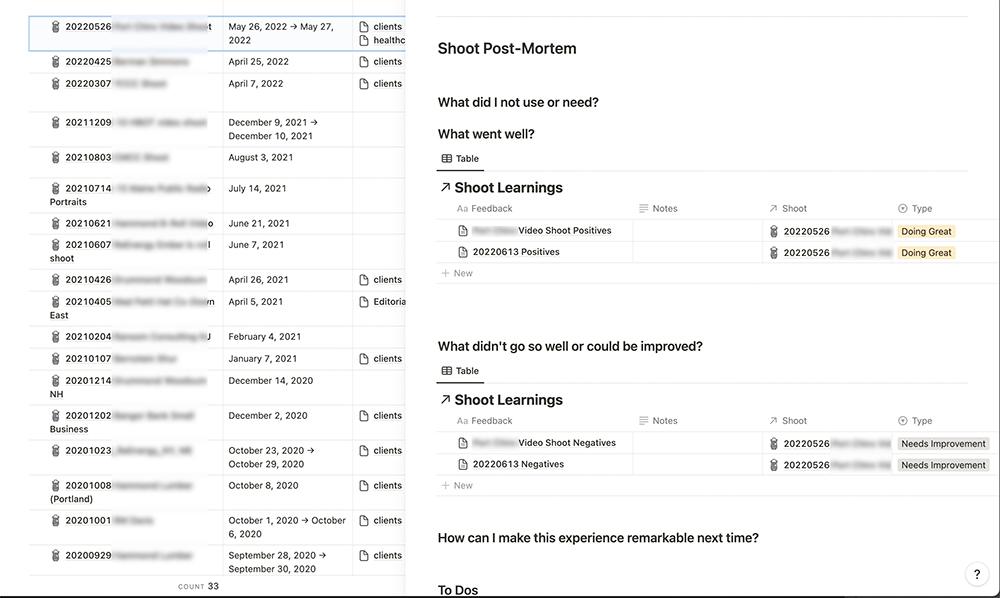

A case in point: a recent shoot went sideways. My first location and setup just wasn’t working the way I wanted it to. Then, my subject got pulled into a surprise last-minute meeting. This chewed up one hour of a two-hour shoot. Fortunately, I’d arrived hours before the shoot and had other setups and locations waiting. I pivoted, and once my subject was free, we were able to move on.

Those second and third locations turned out to be gold. Far better than the original, in fact. Redundancy gave me options, which in turn gave me the ability to adapt. Challenges are a certainty in any business. But if you give yourself options, you’re not just surviving—you’re thriving when things change. Maybe it’s better to reframe redundancy. Rather than being expendable, it’s about being prepared.

–30–