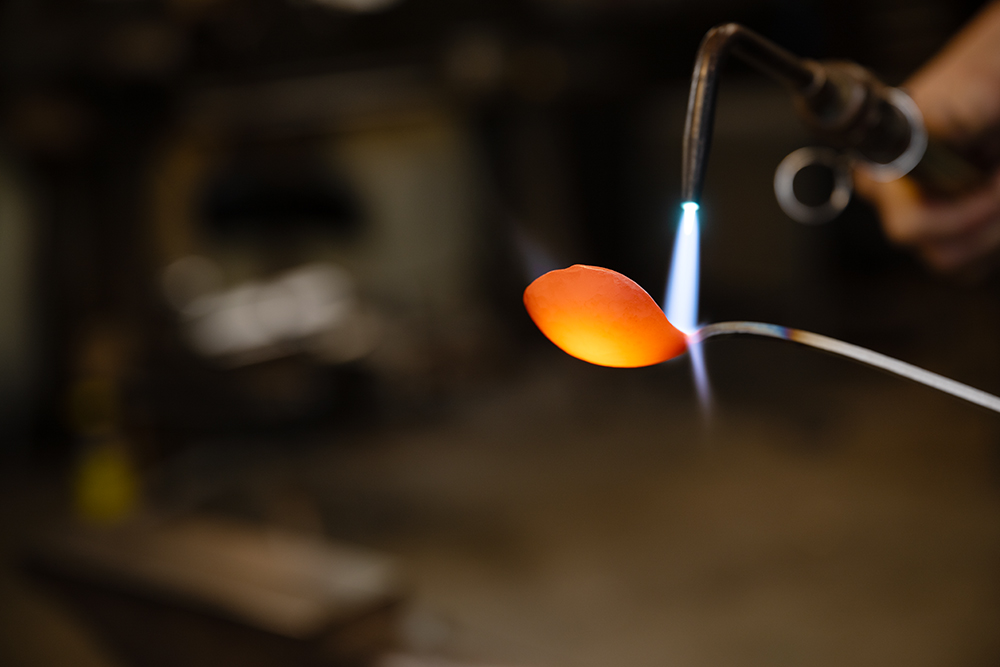

As part of my ongoing Creating Spaces series featuring Maine artists in their working environments, I had the opportunity to work last fall with Heide Martin and her husband, co-founder Patrick Coughlin. The couple operate Rockland, Maine-based Heide Martin Design Studio, creating unique and functional furniture and housewares.

I was drawn to the studio because of the strong sense of style that permeates their work. Working with natural, simple materials available here in Maine, the two produce exquisite pieces of art that happens to double as functional furniture.

In particular, I love how Heide incorporates the art of weaving into many of her pieces, drawing for inspiration from an out-of-print book on traditional weaving patterns, among other sources.

I’m happy to be able to show the video we produced that day, along with a few stills from my visit with Heide and Patrick in their spacious and well-ordered studio.