The last thing I wanted was to be seen.

Not for something like this, completely out of my control.

Many people get cancer—an estimated 2 million in the U.S. alone 2024—but every story is unique.

My own cancer came in late 2015. A routine scan for a kidney stone led to surgery, and suddenly, I was missing part of my right kidney. A rare cancer, they told me. No apparent cause, no warning.

Then, it was over—the surgery, at least—but not the worry, the scans, or the realization just how fragile life is.

I minimized it and took to calling it “cancer with a little ‘c'”. But it definitely changed me and still does.

There’s a moment when we all have to face our mortality and that was mine. My wife went back to school to retrain for a job, in part to support us in case I had a recurrence.

I dealt with it by throwing myself into work and filling my life with trivialities and busy work.

But every time I looked in the mirror and saw the scars—or felt the phantom itchiness as my scars continued to fade—I was reminded: it could have ended up so differently.

In 2020, I saw Trevor Maxwell’s name come across my feed. Trevor and I had worked together briefly at the Portland Press Herald. He was younger than me, a dad with two girls, a husband. And now he had stage IV Colon cancer.

I regret that I didn’t contact him right then. What do you say to someone fighting for their life? Months later, I saw that he was starting a podcast—Man Up to Cancer. A space for men facing cancer to connect. A brotherhood.

So I reached out. We talked about his fight—not just one battle, but many. I photographed him under the ancient oak tree on his family property he called his shield. Trevor mentioned his scars then. Not as things to hide, but to celebrate.

That’s when Baring Scars was born.

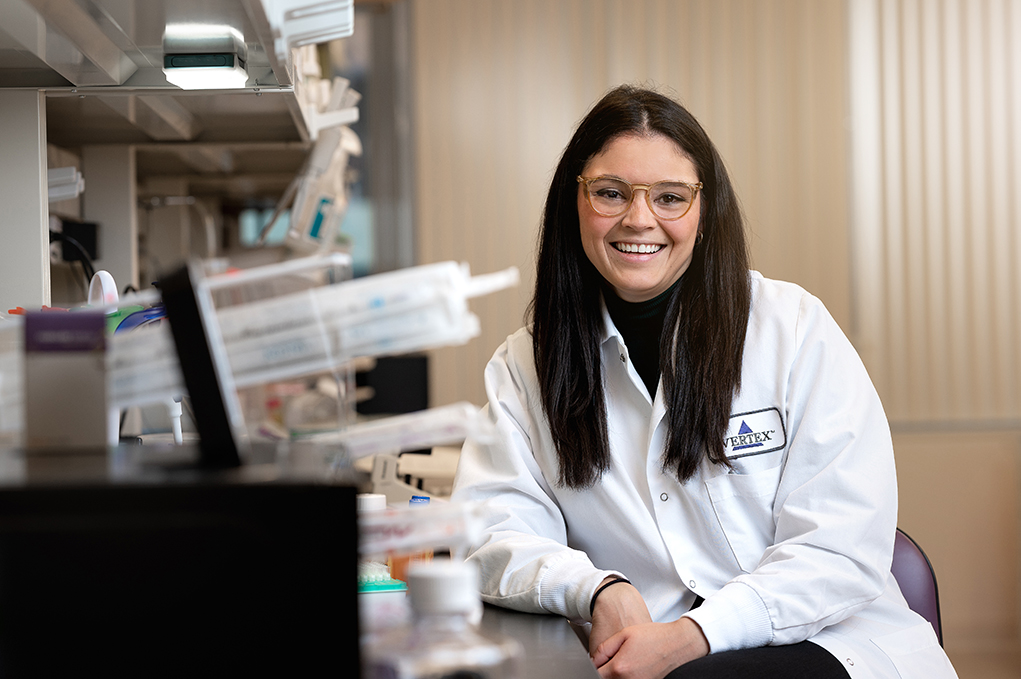

The idea: Photograph 50 men with cancer. Let them tell their stories. Show their scars—not just the physical ones, but the strength, uncertainty, and resilience they carry. Isaac Marston, whose photo is above, was the first person I photographed (read more about Isaac’s story here).

Men have worse cancer outcomes than women. Not just because of biology, but because of how we deal with illness. We tend to ignore pain. To delay seeking help. When diagnosed, we isolate.

Baring Scars challenges that. It’s about connection. A visual statement: You are not alone.

At first, I wasn’t sure men would step forward. But they did, over and over. They told me this was self-empowering. That they wanted other men to see what survival looks like. That they wanted to inspire others to keep going.

This project is for them. For the men fighting cancer right now and for their loved ones. For the organizations working to change outcomes. For the men who think they are alone.

If it encourages even one man to seek help, to get screened, to reach out—it will have been worth it.

–30–

© Brian Fitzgerald

© Brian Fitzgerald