Most of the work I do involves telling the story of people at work, usually in changing and varied environments. I can think of few environments nicer than being out on Casco Bay on a hazy, sunny spring morning.

Recently I spent a morning on a boat operated by the Southern Maine Community College Marine Science program. Instructor Brian Tarbox led a group of students as they performed a routine survey of Casco Bay, sampling water temperatures and collecting other data.

Many people might be surprised to know what a great, and affordable, educational resource SMCC is. Situated on a beautiful stretch of waterfront in South Portland (formerly the site of Fort Preble) it offers coastal views that any college–community college or university–would envy.

Here are some more images of SMCC.

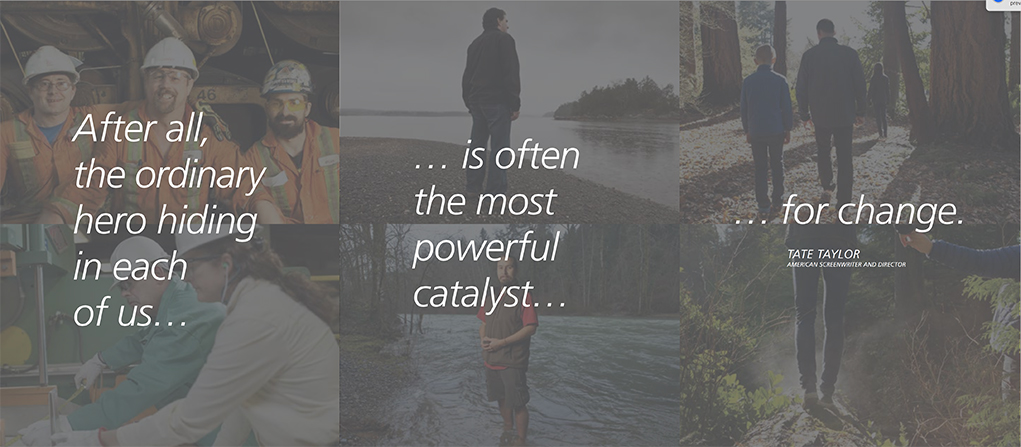

This spring and summer I had the pleasure of working with the amazing

This spring and summer I had the pleasure of working with the amazing

ials that highlight the work the company is doing to better manage resources, be more efficient and safety-conscious. The images themselves tell a story about the connection the company fosters–with the communities they live in, the people that work at the plants, and with the environment that makes their products possible.

ials that highlight the work the company is doing to better manage resources, be more efficient and safety-conscious. The images themselves tell a story about the connection the company fosters–with the communities they live in, the people that work at the plants, and with the environment that makes their products possible.