[photoshelter-img width=’500′ height=’352′ i_id=’I0000w85MS3SOAJM’ buy=’0′]

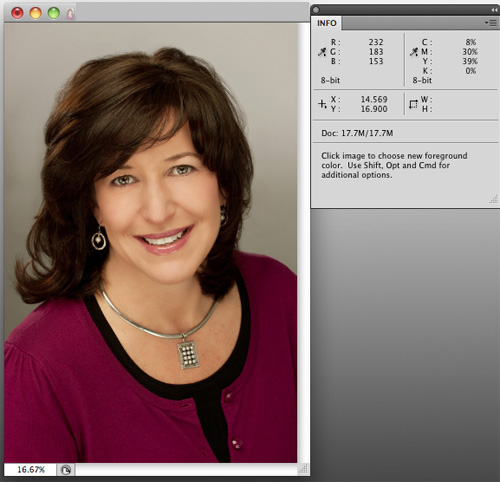

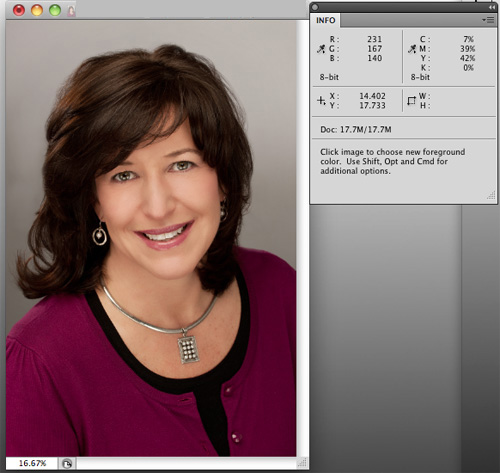

I get the feeling my corporate and entrepreneur clients are thinking this when I’ve delivered a job to them.

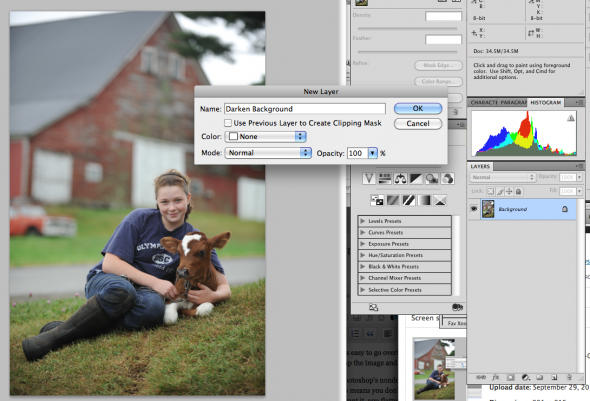

My deliverables may include DVDs of high-resolution images, a “READ ME” file explaining color space, file format, etc, and pdf contact sheets. Beyond that, I often post images in a protected gallery on Photoshelter, my online image library. Each file I deliver is typically a high-resolution, 300 dpi color file, saved either as .jpg (compressed) or a .tif (uncompressed). Think of it as a master file. From this high-quality original file, clients can output the image in a variety of ways for specific uses including:

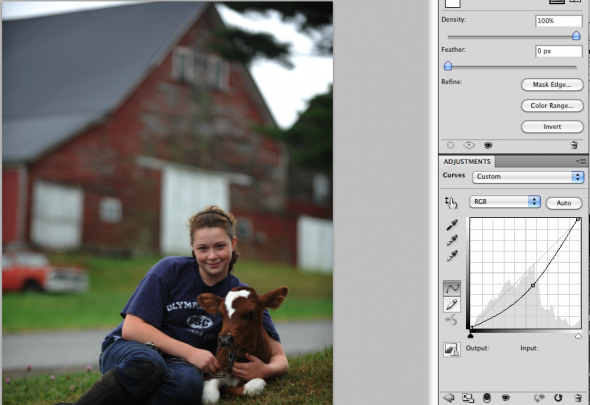

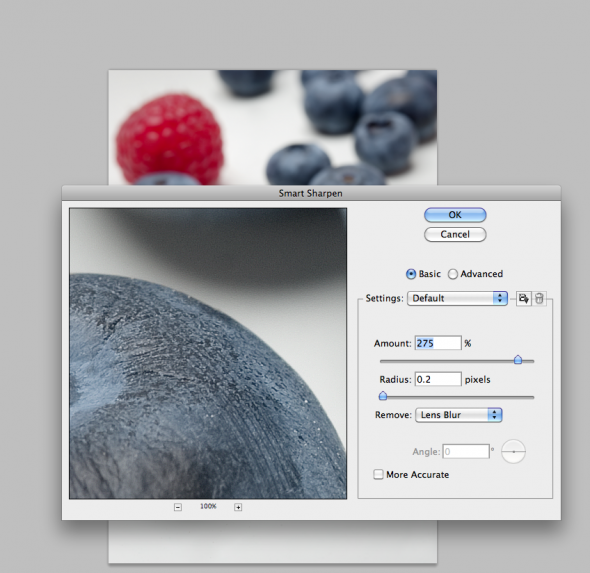

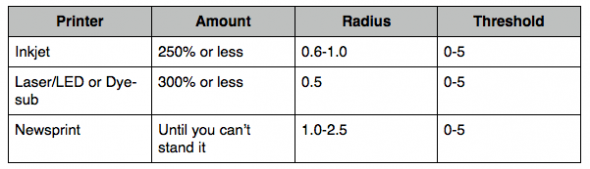

- Newsprint: Most newspapers have a line screen of 100 lpi (lines per inch) or less. Double this number to get the necessary resolution, or dpi (dots per inch). In addition, newspapers are printed on an offset press that uses four colors, so ideally you’d convert your file’s color space from RGB to CYMK. Reds, blues and other colors can dramatically be altered during this conversion process, which may require additional imaging work to recover the brilliance and colors of the original image. Lastly, because newsprint absorbs ink, photos destined for a newspaper require quite a bit of sharpening (much more than a print on photo paper) in order to look clear, sharp and bright in your average newspaper. Most newspapers will accept any kind of high-resolution digital file, and then do all of this work for you. If you want to make sure it’s correct, we can do it as well.

- Photo Prints: Most pro labs require resolutions of 240-300 dpi, so your image will automatically work great for that. To really make it pop, it’s good to do a little bit of sharpening to your image. It’s also useful to soft-proof the image on a color-calibrated monitor–ideally after embedding the correct .icc color profile built for the specific printer you’re using. These are available often from the printer themselves, or you can download them here: Dry Creek Photo.

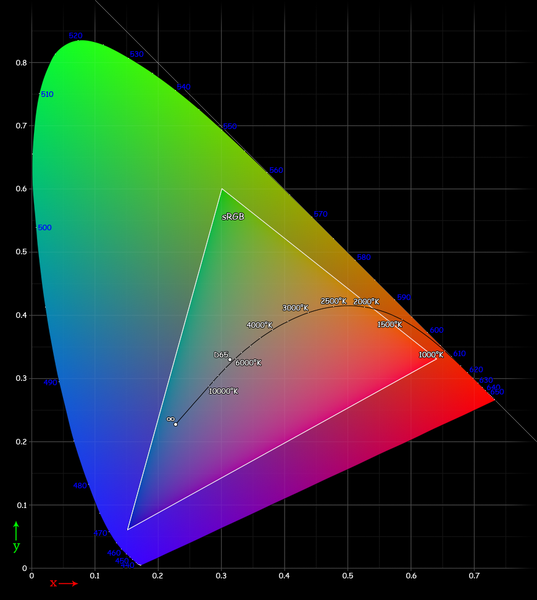

- Web: Since the web is viewed on machines and screens of all types, it’s not impossible to make your image look great on every one of them. Make sure you have a fighting chance by converting your file to the sRGB color space, or otherwise it may look too yellow or magenta on PC screens.

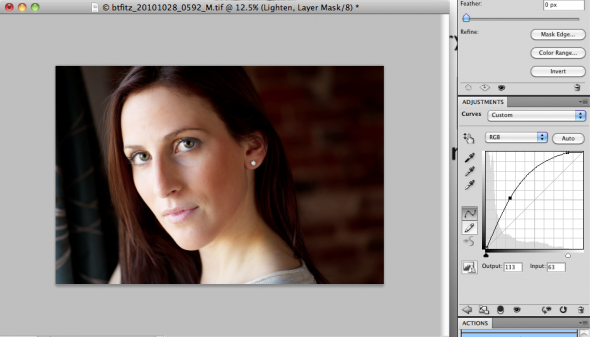

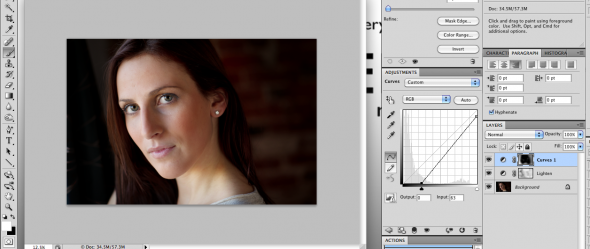

- Black and White: If your image needs to be turned black and white, you could just do an automatic grayscale conversion in Photoshop or even in free editors like iPhoto and Picasa. It’ll work, but it’s not optimum. My preferred way is a multi-step process that preserves detail in shadow areas and gives a much richer tone to the finished black and white image.

- Upsampling: If you need to make a print that is physically larger than the size of the digital image, you have a few choices. You can resize the image to the larger size, but if it’s more than 10% larger than the original you’ll get pixelation and softness. Again, I use special software to upsample the images to larger sizes in a way that preserves the image’s integrity as much as possible. Keep in mind that when you size a photo up, you’re asking the software to add more pixels. These have to come from somewhere, so basically the software takes a look at the color of the existing pixels and makes an educated guess about what color pixels to add to generate the larger-size photo. Depending on the sophistication of the software, this can be done well or very badly.

It can be daunting when you aren’t sure exactly how to use the image files in an optimum way for each specific application, be it web, newsprint, photo print or other. Knowing how you’ll use your images, and communicating that to your designer, photographer or programmer , is key to your success. As part of my service, I’m happy to help my clients optimize their images for use in magazines or the web.