We’re just a couple of weeks from our Traveling Light Workshop, and as a lead-in I’m previewing some of the topics and shoots we’ll cover during the three-hour class.

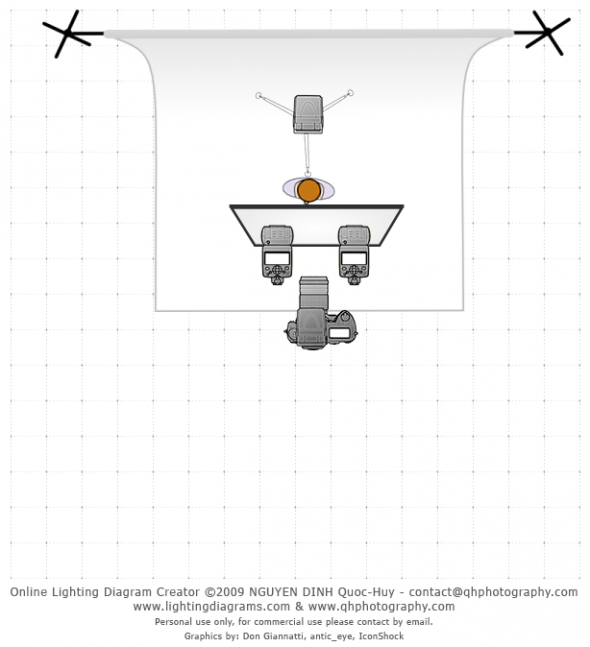

You can’t discuss portable lighting without getting heavy into some nerdy gear discussions. So, we’ll be talking plenty about triggering your flashes using manual and auto triggers—everything from old-school sync cords to off-camera TTL cords, from optical slaves to Pocket Wizards and Radio Poppers.

But it’s not all about gear. It’s also about technique—how you approach a shoot and what works best for different situations ‘in the wild’.

As always, the best system for you is the one that fits your budget and allows you flexibility in lighting on location.

I’ve gotten requests from people who want to bring their flashes and other gear. Great! We’ll discuss those and, time permitting, will give hands-on demos with your gear.

If you have any questions about off-camera lighting that you want to make sure we cover, shoot me an email with your feedback.