The background as subject

One of the greatest tools in a location portrait photographer’s toolbox is the context provided by the shooting location. For example, a portrait of a person standing in a long hallway covered in glass windows. The environment—the glass windows and long hallway—conveys potentially important information about the subject. It also gives the final portrait mood—in this case it might be bright, open, cheery, confident, clean, modern and contemporary. Obviously, the right background is extremely important to a portrait. It does a lot of work that propels the portrait or the image..or, conversely, can sink it. The “environment” part of an environmental portrait is so critical that I think of it as the second character in the room—equally important, in terms of attention and consideration, as the human subject in the frame.

Missing Context

Until it isn’t.

Backgrounds are very important, but photographers can’t always rely on having them. Often, the backgrounds convey the wrong information, give the wrong mood, or need to be mitigated and modified. Sometimes, the background is intentionally removed from the equation entirely.

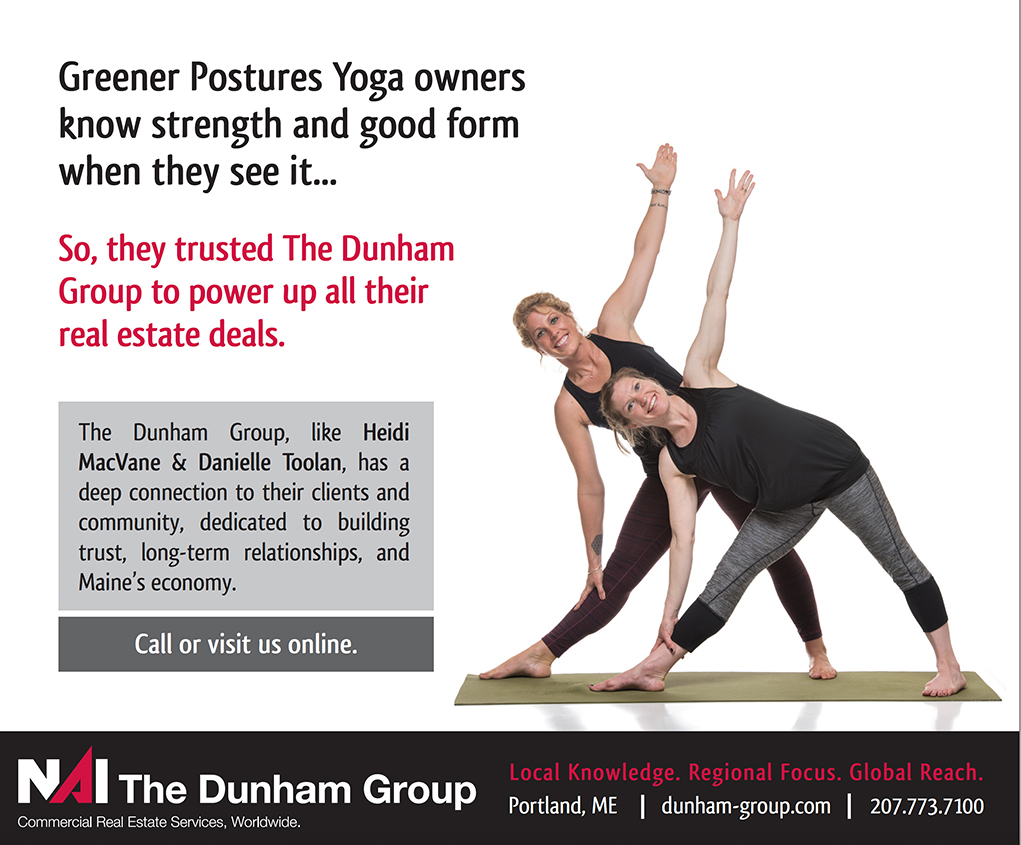

This was the case with a recent shoot. I worked with Maggie Hoople of East Shore Studio & Print on an ad campaign for NAI The Dunham Group, a large commercial real estate broker based in Portland, ME. The ads would feature the owners of interesting Maine-based businesses who leased their commercial spaces with the Dunham Group’s help. We’d done the same campaign previously, featuring solo individuals. This time, each image would feature the two partners who ran each business.

Since these images would be used in a variety of ways from print ads to large displays at the airport, on buses and elsewhere, they would need to be photographed as full-body portraits on a white seamless paper background. I’d have to rely on really engaging with the subjects since the mood and emotion of each ad would have to come purely from them. The bright white background, though featureless and without context, still would convey a bright, optimistic, clean and modern look.

Fascinating Subjects

It was a fun shoot. Business owners are fascinating people, by nature optimistic, dynamic people who have a passion for what they do. People like Kate and Steve Shaffer from Black Dinah Chocolatiers, Peter and Noah Bissel of Bissel Brothers Brewing, Heidi MacVane and Danielle Toolan of Greener Postures Yoga and Ben Waxman and Whitney Reynolds of American Roots. The shoot was an exercise in making them feel comfortable enough that they could forget about the background, and the lights, and the setting, and to focus instead on their accomplishments, their motivations and their business plans. Having two people in the frame provided a great opportunity for interactions, too, leading to serendipitous, unscripted moments, and key props and clothing helped give clues that the background couldn’t provide.

Backgrounds are nice…but it’s always about the subject

So without the context of a background, it’s an opportunity for photographers like me to dive in and go deeper with my subjects. Freed of obvious visuals, the challenge and the reward comes from telling a story through moments that change from second to second. To me, that’s what it means to be a photographer of people. It reminds me that even when there is an interesting background in the frame, the focus should always be on the people in front of the lens. The emotional impact of the portrait comes from them, and that will make an image fly or fail no matter the background.