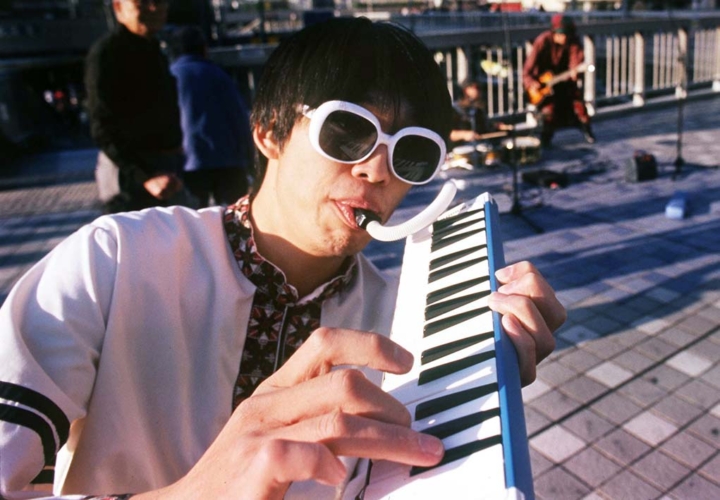

Work. It’s always been a big focus of my life and definitely a focus of my professional body of images. I photograph people at work, doing work, and showcasing the results of their work. Work—hopefully, meaningful work—gives our lives value and helps us get up in the morning, ready to put in long hours away from family, from home and from friends. I’m fascinated by what drives people to give so much blood, sweat and tears to companies they own or companies they punch a clock for.

To me there’s no better lens through which to view our changing society than by photographing the work people do and how they do it.

This is one of my favorite portraits from the last year, part of a series of images (here and here) documenting the changing look and feel of the modern workplace. It’s of Nate Tower, who leads marketing strategy efforts at Energy Circle, a marketing and technology company and one of the fastest-growing businesses in Maine in 2016.

Stay tuned to this blog for additional work that I’ll be rolling out throughout 2017, showcasing the interesting workplaces…and the people I find there.