For the first time, I’m publishing a few images from a project on Maine’s Peace Officers that I’ve been working on for over a year with the working title, Arrested: Stories Behind the Badge.

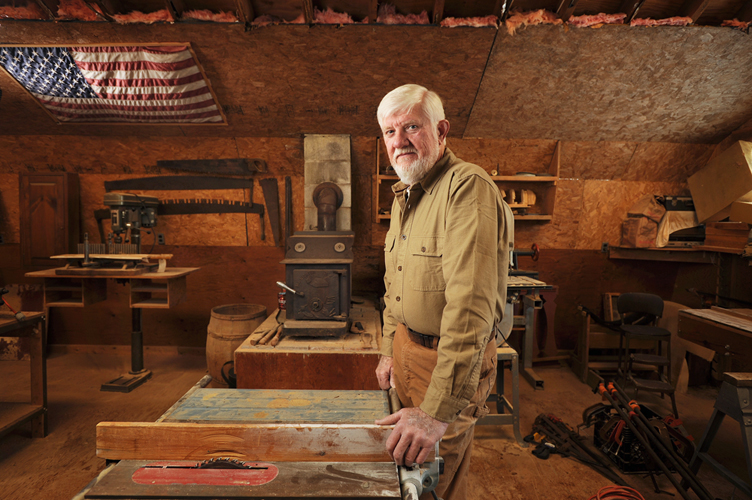

‘Arrested’ is a series of portraits of law enforcement officers from across the state of Maine, photographed at the actual locations where they experienced a life-altering incident on the job.

The diversity of situations the officers I’ve interviewed have been incredible: some have been shot; others have had to use their weapons. Some have been injured, some have saved lives. All have had to react in situations that required skill, judgement and humanity.

Nationally, the idea that cops are dangerous and out of control, and are to be feared–this is an additional burden on officers in Maine, many of whom police the same communities they and their families live in. When a difficult incident occurs, they are reminded of it every time they pass the spot where it occurred.

This project is an attempt to convey the reality of the difficult work officers do every day. I’m thankful to the officers who have participated. I’d like to say that it’s been a good experience for them to share their stories, but I also know it’s not been easy for people who tend to avoid the spotlight.

It’s been an incredible experience for me as well and I hope to share the complete project, as well as the many stories, soon.